Reserved Channel: Reconnect, Revitalize, Regenerate

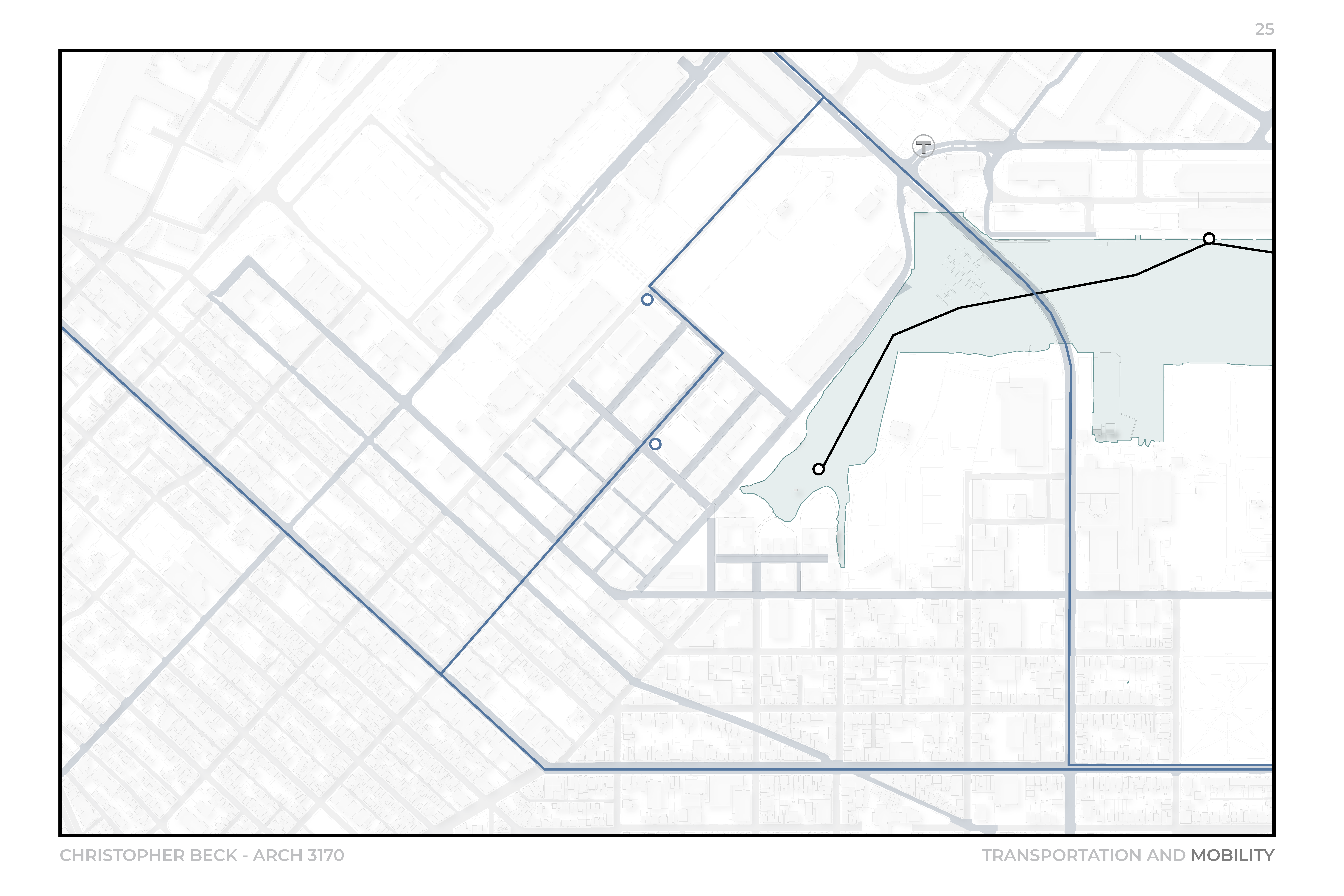

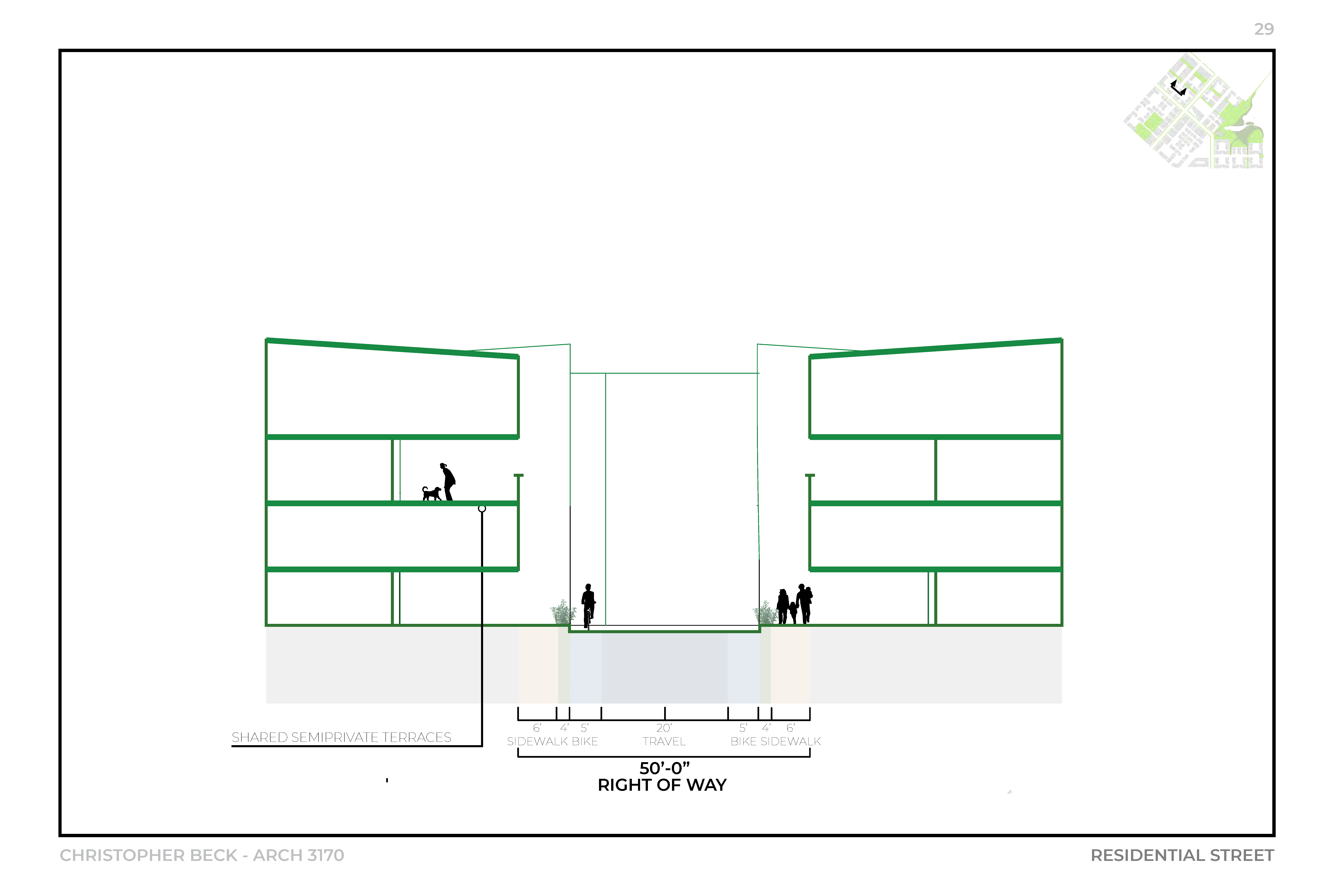

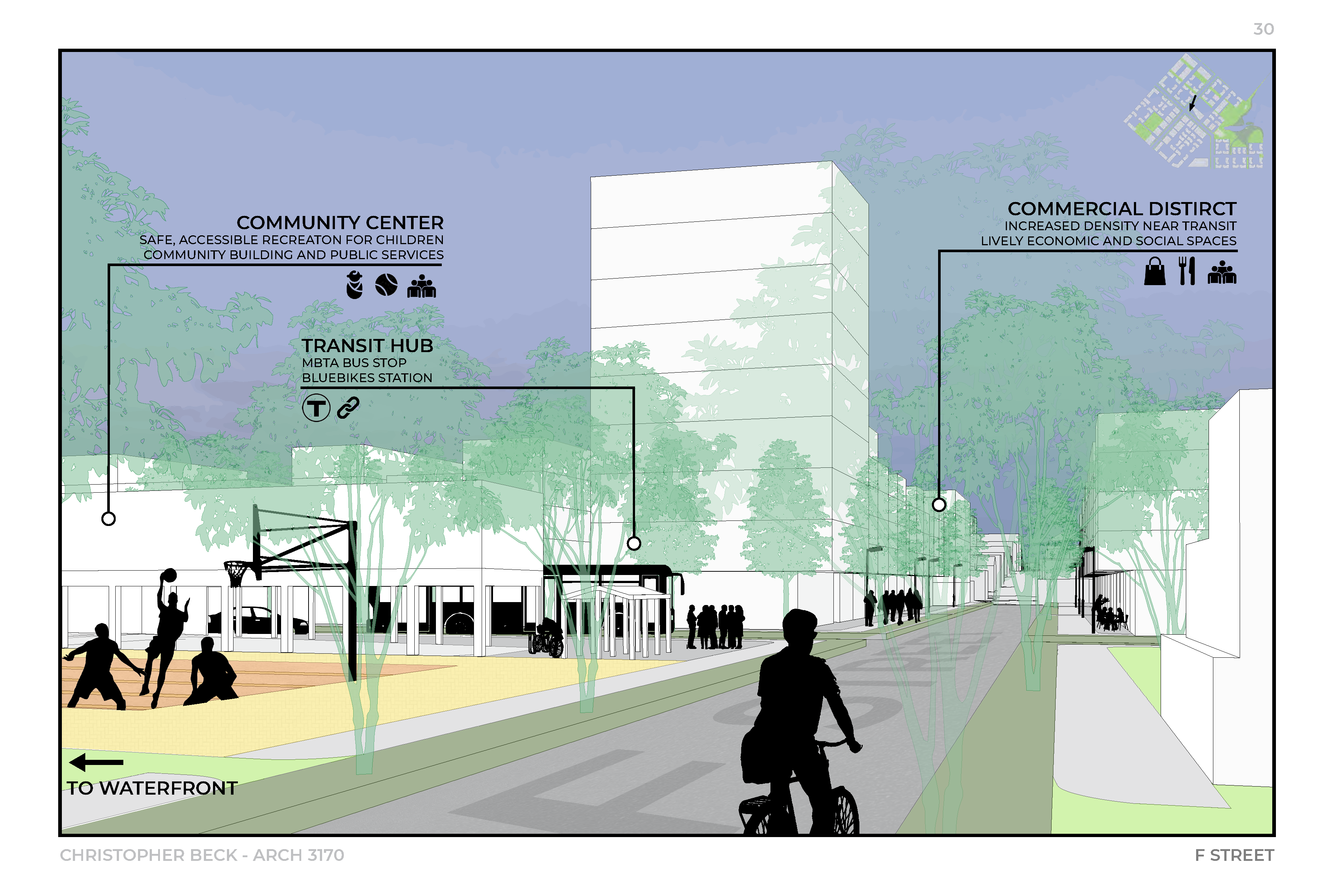

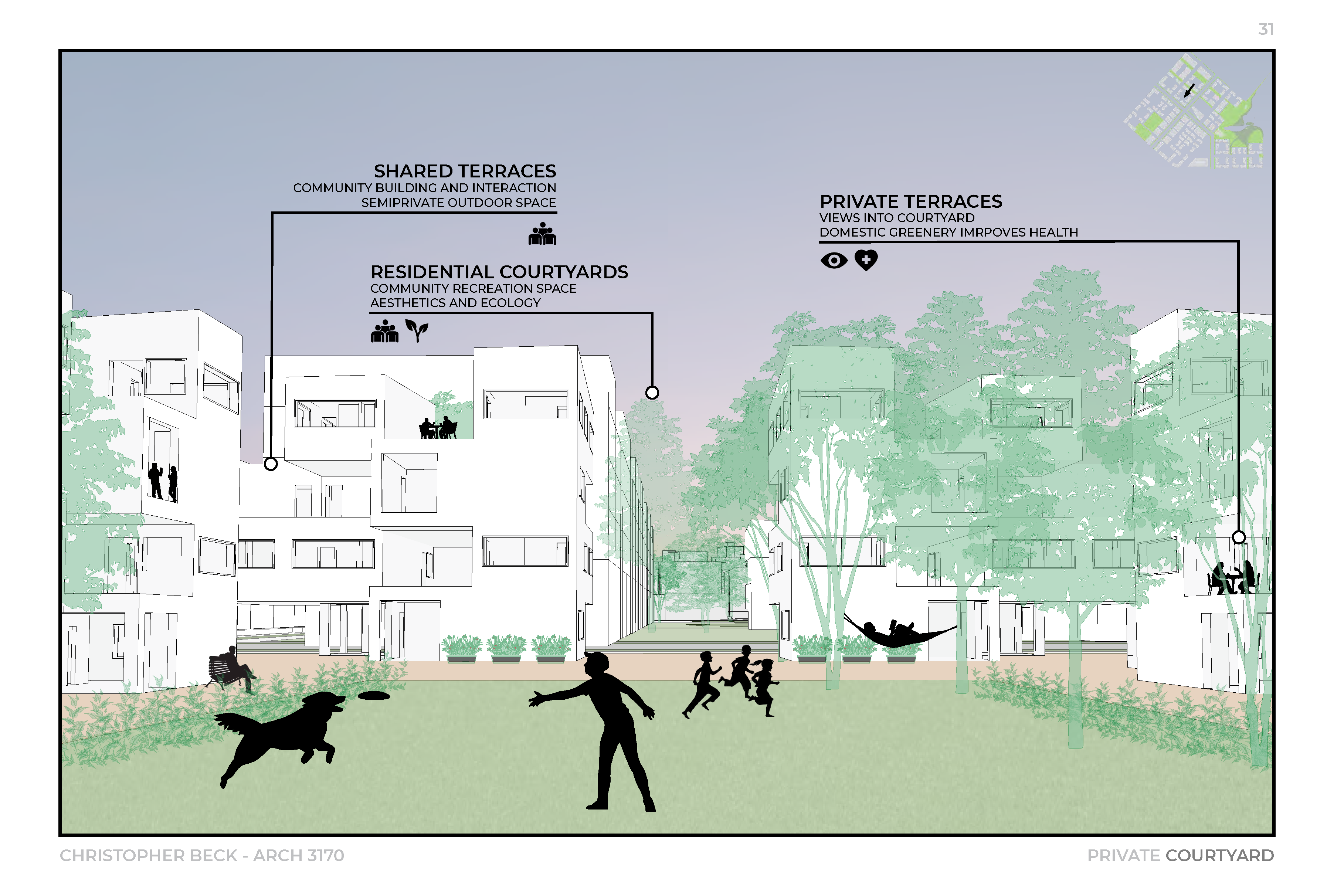

Reconnect, Revitalize, Regenerate is an ambitious mixed use neighborhood proposal at the head of South Boston’s Reserved Channel which expands on the City of Boston’s Climate Ready South Boston initiative by integrating working landscapes which mitigate flooding and rehabilitate soil while providing recreational and community-building opportunities into the existing network of Boston’s open spaces. It is bolstered by a series of public amenities, transportation infrastructure and economic development which provide for a historically underserved and isolated area and reconnect it both physically and socially to the greater Boston community.

Site Analysis and Project Overview

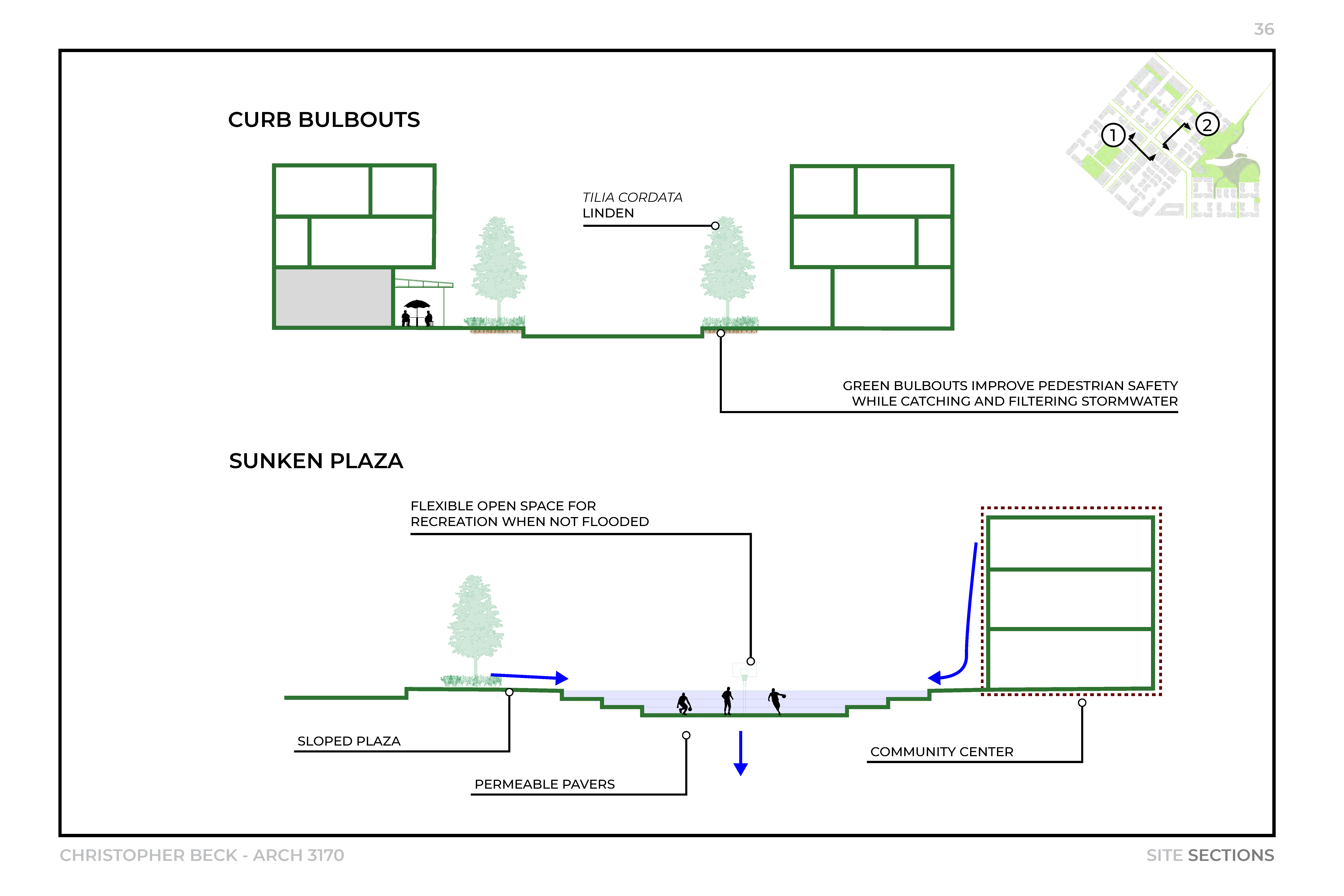

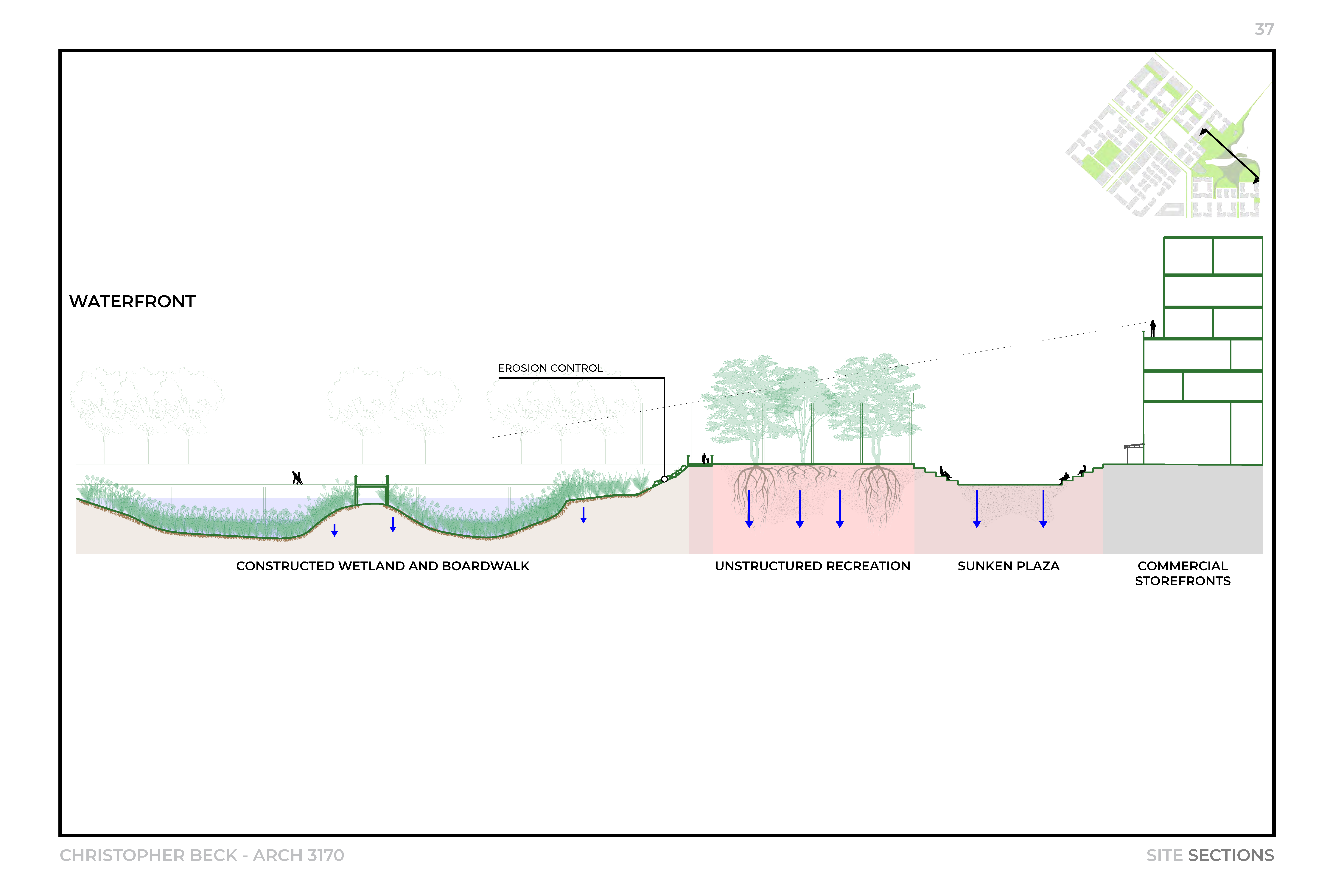

Our site is on almost entirely infilled land, meaning that its soil is highly impermeable, poorly drained, and flat. If sea level rise continues at its current rate, it will be entirely submerged. Even before climate change, existing flood patterns already cause water to pool on the site; climate change will only exasperate this. In addition to flooding the site also contends with lead contamination in the soil, especially on the southern side of the site. The City of Boston is aware of these issues and is proposing, in dialogue with residents, natural flood mitigation and green infrastructure spaces such as living shorelines and boardwalks that also serve community and recreation functions.

The site also sits at a point of transition and of tension – between old and new urban fabrics, between residential, industrial and commercial-dominated uses, and between different demographics and cultures.

Three-Pronged Planning Approach

- Reconnect the site to the greater area of South Boston, both physically and culturally.

- Revitalize lost community and social infrastructure.

- Regenerate the environment and economic opportunities.

Design Proposal

Click here to view the project in more depth, or see the highlights below:

Work with Build Health International

My professional work with Build Health International, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Beverly, Massachusetts, includes four major projects over the span of a year and a half, from July 2020 to the end of August 2021. Visit https://www.buildhealthinternational.org/projects/ for these projects and more of their work.

The Koidu Maternal Center of Excellence is a state-of-the-art maternal health complex in the Kono District of Sierra Leone, the first of its kind in the nation. On this project, I contributed to the design of the main waiting

pavilion and other outdoor spaces including a comprehensive planting design scheme, the design of the roof structures for various buildings of the complex, as well as the cataloging and preparing the layout of medical equipment and furniture.

The Hôpital Universitaire de Mirebalais, which is located in the Mirebalais Arrondissement of Haiti’s Centre Department and opened in 2013, is the largest public hospital in Haiti. In 2021, a small BHI team designed a new diagnostic center addition for the complex equipped with an x-ray and CT scanning space. I was one of three on the architecture team, and contributed to the design of the facades, roof structure, building and equipment layout, and connection to existing structure; as well as research and detail work pertaining to the radiation-shielding of the screening spaces.

Wesleyan Hospital is a large teaching hospital owned by the Wesleyan Methodist Church, near the city Anse-à-Galets on the Haitian island of La Gonâve. BHI is developing a master plan for the hospital, which had been struggling due to inadequate infrastructure, lack of medicinal resources and facilities, and the COVID-19 pandemic. I contributed to the master planning report, including creating site analysis and preliminary development strategy diagrams, writing text, and formatting the report.

St. Rock Hospital is an addition to an existing clinic in Carrefour, a suburb of Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital. The existing clinic has inadequate space and resources to treat Carrefour’s population of over 500,000, a critical need that this new development will address. It is expected to increase the facility’s capacity by over 400% and provide new facilities for much needed types of care including HIV, dentistry, and mental health.

Renderings and photos of the Maternal Center of Excellence. Via Build Health International and Partners in Health Sierra Leone. See https://www.buildhealthinternational.org/project/maternal-center-of-excellence/ and https://www.pihsierraleone.com/mcoe for more information.

Planting plan of Maternal Center of Excellence campus.

Wrapped Like a Prized Gift

A research paper written about Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s 1995 project, Wrapped Reichstag.

I. Introduction

Wrapped is a series of temporary art installations that were created by Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (1935–2009), beginning in the early 1960s and continuing to this day. These projects consist of various objects wrapped in fabric, so as to remove their defining features. The pair began with small everyday objects and furniture but quickly moved to more ambitious projects such as “wrapping” the Reichstag Building in Berlin, Germany, in 1995, in over 100,000 square meters of silver fabric. According to an Art News article published after Christo’s death in May 2020, the wrappings have the goal of “effectively deconstructing and reconstructing the way we think about how those structures function with respect to their surrounding landscapes”.[1] Obscuring all but the general form of an object gives it a different relationship to its surroundings. It appears as a distinct object set apart from the landscape, void of context and waiting for its meaning to be filled in.

The Wrapped Reichstag helps the West move on after the Cold War by transforming uncertainty and pain into optimism and hope, and has had a lasting impact on architecture’s relationship to popular culture in the twenty-first century. The project created an aura of joy and light-heartedness that permeated every level of Berlin’s society despite the tension of the Reunification process. The ephemerality of the installation reminds us that past pains and fears are finite and can be moved on from, and its profound symbolism of rebirth and renewal has made its way into both contemporary art and architecture, and broader popular culture.

[1] Greenberger, Alex. 2020. “Christo Dead: Famed Sculptor Dies of Natural Causes at 84.” ARTnews.com. ARTnews.com. May 31, 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/christo-dead-wrappings-sculptures-1202689250/.

II. Background (1884-1989)

The Wrapped series was conceptualized in 1958 when the Bulgarian-born Christo and Jeanne-Claude, the daughter of a French-Moroccan military family, began experimenting with wrapping household objects in various materials. Rejecting the rigidity, strictness and, repression of their respective backgrounds, they joined the French avant-garde art scene seeking artistic and personal freedom. As students of the Situationist and Nouveau Réalisme movements, they were fascinated by the concepts of changing the way reality is perceived and the subversion and hijacking, or détournement, of the status quo. Christo produced Project for a Wrapped Public Building, the first iteration of a concept that would become his life’s work and magnum opus, in 1961. The piece is a collage of a large rectangular building draped in cloth which stands in stark contrast to the “otherwise ordered urban environment.”[1] In seeking to create a landscape that breathes new life into an existing order, they likely could not have found a better canvas than Berlin’s Reichstag.

Berlin in the late 20th century is the place where Western decadence and consumerism and Communist uniformity and oppression meet, and the Reichstag is the most charged building in the city. The Reichstag was constructed beginning in 1884 under Kaiser Wilhelm I by the Frankfurt-based architect Paul Wallot to be the seat of the Imperial Diet. The project was controversial and marred with political and bureaucratic pressure that eventually created an assemblage of different styles that left few satisfied. After Wilhelm II abdicated following the German Revolution of 1918, Phillipp Scheidermann proclaimed the Weimar Republic from the building’s balcony. During the turbulent years to follow, it would become the site of protests, massacres, and unrest culminating in the Reichstag Fire of 1933, which was used as a pretext by the Nazi Party to effectively abolish the Republic. When Berlin fell in 1945, the building was abandoned and was still in that same ruined state when the eccentric artists first pitched their proposal to a stunned West German Parliament at Bonn in 1976. Though this first proposal failed, the artists continued to work towards it until 1995 when the “essence of the Reichstag” would finally be revealed.[2]

[1] Swartz, Anne. “Christo and Jeanne-Claude.” The Encyclopedia of Sculpture (2004): 317-320.

[2] “Christo and Jeanne-Claude.” christojeanneclaude.net. 2021. https://christojeanneclaude.net/artworks/wrapped-reichstag/.

III. Reunification (1989-1995)

Berlin at the end of the 20th century was a city full of tension, discomfort, and uncertainty. The preparation for Reunification involved a significant overhaul of the city’s infrastructure, and the question of how to reincorporate 16 million people from a country that was economically and culturally stuck in the 1950s loomed large in the minds of politicians and citizens. In the background of all of this uncertainty, there was still the lingering pain of the World Wars, the confusion about what German identity post-reunification would look like, and other nations’ fears about the possibility of this united, economically powerful country causing even more bloodshed in the future. In a way, this tension and discomfort was the perfect backdrop for such an outlandish project. East German journalist for Der Spiegel, Monika Maron, wrote that the proposal barely phased her when she first heard about it, as “the absurdity of the Berlin Wall could not be surpassed, only added to.” In contrast to the Wall, the Wrapping of Germany’s most important building “struck me as perfectly logical.”[1]

The Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989, and Berlin suddenly was thrust back into the spotlight as one of Europe’s economic and cultural centers. For almost fifty years the city was “a showcase for competing political ideologies” where East and West violently collided. Not willing to keep that stigma, Berlin underwent a massive program of urban reinvention. Two schools of thought emerged about how the city should progress, one based on conforming to modern sensibilities and the other on preservation and adaptive reuse.[2] As such, the Reichstag, though free of much of the bureaucratic squabbling that defined urban planning elsewhere in the city, was pressured by these political interests and Norman Foster’s restoration was forced to take on certain elements that limited his creativity. Still, Foster managed to get his message across, and one can see the continuity between his messaging and the ideas Christo and Jeanne-Claude were also trying to present. The new design demonstrates “an understanding of history, a commitment to public accessibility and a vigorous environmental agenda.” Journalist Deyan Sudjic said that the restoration is both “a memorial to the past [and] a departure from history.”[3]

Similarly, the debate of Historikerstreit had been raging since the 1980s. The question of how Germany should view the atrocities of the Nazi regime, which had broader implications of how other countries should view their past, was fiercely debated. The main disputes included whether the Holocaust is unique in history, whether there is any sort of moral equality between the crimes of the Nazis, the Soviets, or even the Western Allies, and whether nationalism is acceptable in a modern, globalizing world.

[1] Monika Maron, “A Gigantic Plaything” [“Ein gigantisches Spielzeug”], Der Spiegel, July 3, 1995, pp. 24-25

[2] Rogier, Francesca. “Growing Pains: From the Opening of the Wall to the Wrapping of the Reichstag.” Assemblage, no. 29 (1996): 44-71. doi:10.2307/3171394.

[3] Douglass-Jaimes, David. 2018. “AD Classics: New German Parliament, Reichstag / Foster + Partners.” ArchDaily. October 25, 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/775601/ad-classics-new-german-parliament-reichstag-foster-plus-partners.

IV. A Controversial Installation

As the Bundestag was preparing to move the German capital from Bonn back to the newly reunited Berlin, Jeanne-Claude and Christo were tasked with inserting an outlandish and light-hearted intervention in the midst of all the tension. They had to contend with various schools of cultural thought and fight through political red tape, all while trying to keep their messaging intact and complementing Norman Foster’s lofty ideals. The moment was over twenty years in the making but it is hard to imagine the project taking place at any other time before or after. Taken together with the remodeling of the building, the movement of the capital, and the new millennium, Wrapped seems to fit perfectly in the timeline. In spite of these optimistic trends, criticism from average citizens all the way up to Chancellor Helmut Kohl himself echoed the idea that German history and the integrity of certain sites are not to be tampered with. But, the artists felt that tampering with these sacred pieces is exactly what the German people need.

Covering up a distinctive building hides its defining elements and invites the viewer to treat it as a blank canvas. All throughout its history, the building was a symbol of authority and propaganda, being used by both Imperial Germany and the Nazi Reich as its general assembly and used for propaganda shows and protests during the Nazi regime and Soviet occupation. It also became a symbol in some of the most iconic images of World War II and the postwar order, including the iconic 1945 photograph Raising a Flag Over the Reichstag, which touts Soviet supremacy and the crushing of the German spirit. Sitting vacant since the Fall of Berlin, the building was asking for a new purpose, and West Germans saw it as a beacon of hope. But it would take a forceful separation from the painful context in order to truly unlock its potential as such a beacon.

Many higher-ups in German society, including journalists and legislators, were hesitant, seeing it as a vanity project. Frank Schirmacher, a journalist from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, famously said of the project in 1994 that it was nur Selbstzweck ‒ “simply an end in itself” ‒ that would only serve to divide.[1] One of the fiercest opponents of it was Wolfgang Schäuble, then a Representative and now President of the Bundestag, who argued that the Reichstag was one of Germany’s few symbols of unity and national pride. “[The Reichstag] should not be the subject of experimentation,” the CDU/CSU leader argued in a fiery speech on February 25, 1994, “wrapping the Reichstag would not unite, it would polarize.” Moreover, the masses will not understand it and it will only confuse and scare them. Vice President Burkhard Hirsch echoed his sentiments, claiming that “in our country, there should and there must still be things that are not available for private pastimes”[2]. These criticisms hint at the underlying unease and fear of the German people at losing what makes them unique in the quest to grow and redefine their identity in the new, modern world. Firing back at Schäuble’s remarks, Peter Conradi of the Social Democrats argued that “this wrapping will insult neither the Reichstag building nor German history […] like a prized gift, the Reichstag will become more valuable, not less”. Conradi gets to the heart of what the artists wanted to create, a respectful and loving act that pushes the country forward and converts the negative energy of historic pains and fears into motivation and optimism for a brighter future. Conradi concludes that Wrapping the Reichstag will be “a positive sign; a beautiful, illuminating signal that fosters hope, courage and self-confidence.”[3] By a vote of 292 to 223, Conradi emerged victorious and preparations would soon be made to wrap the Schloss dem Deutschen Volke in over 100,000 square meters of silver tarp.

Berlin, and the world, waited with uneasy anticipation as over 200 workers covered the Parliament Building with fabric, aluminum, and rope, and the project was unveiled on June 24, 1995. The most liberal estimates guessed that they would have around half of a million visitors – instead, they got ten times that. Monika Maron calls the installation “a gigantic plaything”.[4] The atmosphere of the event was joyful, lively, and light-hearted, and the Platz der Republik felt like a theme park. One could easily forget that just over 50 years ago the city was in ruins and under Allied occupation, and a mere five years ago the physical manifestation of the Iron Curtain stood just east of the building. Early in the morning on June 25, eager spectators broke through the fence, not to do any harm but just because they wanted to touch the fabric, according to a security guard who was present. Security was initially nervous at this development but eventually laughed it off, and it was difficult to find any face not laughing or at least smiling for the next two weeks.

Everyone there, even the sober politicians, elitist critics, and other skeptics, were jovial and optimistic. Everyone who was previously downtrodden used the wrapped building as a “projection surface for everything they miss in their city and in themselves.” More importantly, Berlin could temporarily forget the stress, fear, and confusion that brought it to this point and just enjoy the party, “because it needed a party.”[5]

[1] Frank Schirrmacher, “Den Reichstag verpacken?” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, (23 February 1994).

[2] Jelavich, Peter. “The Wrapped Reichstag: From Political Symbol to Artistic Spectacle.” German Politics & Society 13, no. 4 (37) (1995): 110-27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23736267.

[3] The New York Times. 2021. “Wrapping the Reichstag: Christo Gets a Go-Ahead (Published 1994),” https://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/26/arts/wrapping-the-reichstag-christo-gets-a-go-ahead.html.

[4] Maron, “A Gigantic Plaything”, 24-25.

[5] Ibid.

V. Two Weeks

Though only lasting for a mere two weeks, the Wrapped Reichstag is firmly a part of the building’s history. No matter how small, it is a pivotal stage in the building’s lifespan, just as twelve years of Nazi rule and forty years of communist division are no less significant when held against the over one millennium of German civilization. In a 2019 interview with the BBC, Christo said that that point is the crux of his project. “Th[e visitors] knew that they were seeing something that would never happen again,” he said, “after two weeks, it was gone forever. It cannot be repeated. Something happened which will stay forever in that particular, unique moment.”[1] True to their roots as Situationists, they were using this opportunity to create a Situation, a unique and liberating event that is both extremely fleeting and extremely powerful.

This idea of ephemerality is also precisely why it resonates with the German people so much and why it is so important today. By realizing the fleetingness of historical events and pains, accepting their place in history, and moving forward after them, post-Cold War Germany was able to heal. It helped them come to terms with the atrocities and strive towards a better future. Furthermore, it is a resumption of a history that had been stopped. For many years the Reichstag was doomed to be frozen in time, keeping the building and the people who view it perpetually stuck on May 2, 1945. The country could not heal until the building was allowed to be reborn and continue moving forward in time. According to then-Bundestag President Rita Süssmuth, this project was a chance to encounter “an edifice that is so important both to their tradition and their future” in a new way. The Reichstag was perhaps the only place in the world where past and future coexisted.[2]

One might argue then that the abundant photographs, memorabilia, and merchandise about the project defeat its purpose. As fellow Situationist Guy Debord might claim, the commodification of this work makes it a Spectacle, a surface-level work that appeals to the lowest common denominator and distracts from the larger issues.[3] Paradoxically, however, this “proof of existence” needs to persist. Christo rightly argues that the experience of the Wrapped Reichstag is a fixed moment in time, a specific set of feelings and interactions that only those who were in the Platz der Republik in that historic summer of 1995 will ever know. The same can be said of any historical event, documented or not. For those of us who were not there, we only know of Wrapped via second-hand sources, the same way we know the Fall of Berlin, the Reichstag Fire, and the proclamation of the Weimar Republic. Residue of history is left behind and persists as long as there are people to see it, getting progressively more alien as time goes on, but is never forgotten.

[1] “The Public Art Project That Entranced Post-Cold War Berlin.” 2019. BBC News. June 12, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/stories-48597551.

[2] The New York Times. 2021. “Christo Sets His Sights on Wrapping Reichstag (Published 1993),” 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/01/07/arts/christo-sets-his-sights-on-wrapping-reichstag.html.

[3] Debord, Guy. “Chapter 2: ‘Commodity as Spectacle.’” In Society of the Spectacle. Detroit, MI: Black & Red, 1970.

VI. The Wrapped Reichstag Today

While the idea of buildings serving as symbols, particularly in regards to cultural changes and revivals, is certainly not new, this concept has become much more mainstream in the past few decades thanks in large part to the Wrapped Reichstag. Motifs of the project such as deriving optimism from a building with formerly negative connotations, restoring and modernizing it after a crisis, and an event centered around its symbol wrapping and unveiling, continue to define urban revitalization efforts around the Western world. Similarly, new adaptive reuse projects take inspiration from Wrapped in their attempts to balance respecting the historic character while also creating something wholly new, and the public continues to be fascinated by projects that obscure or distort architecture to convey a political or cultural message.

One such building that could be seen as a spiritual successor to the Wrapped Reichstag and that embodies many of the concepts popularized by the project is the Louisiana Superdome, a football stadium in New Orleans. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, the costliest tropical cyclone in history, touched down in New Orleans. The city was far from prepared from such a massive storm, and it left severe damage that persists to this day. The stadium was used as a shelter of last resort for over 20,000 residents who could not flee the city. The lack of supplies, the rampant crime within the shelter, the caving of the roof, and other issues, caused the Superdome to become associated with despair for the city.[1] Though expected to take over 3 years, the stadium’s restoration was finished in time for the New Orleans Saints’ home opener on September 25, 2006. This now legendary, aptly named “Rebirth Game” was an event on par with the Wrapped Reichstag, and began with a symbolic unveiling of the gate which was draped in black and gold fabric. The event included concerts, a coin toss by President George W. Bush, and the then-largest viewership of any NFL game in history.[2] As the city healed and celebrated a symbol of pain transformed into a symbol of hope, the former worst team in the league soon rocketed to a Super Bowl championship in 2009. The restoration of the Superdome represented a rebirth and optimistic future for not only the team but the entire city.

Architecturally, the concept of a building veiled and transformed can be seen in some modern adaptive reuse efforts, such as the restoration of La Samaritaine in Paris, France. A former department store that was closed for safety concerns in 2005, it was restored by the Japanese architecture firm SANAA and the French architects Édouard François and François Brugel. The building was renovated and restructured into a complex with a hotel, a department store, social housing, offices, and a nursery. The historic Art Deco and Art Nouveau façades are restored and encased in a rippling glass wall which allows the existing facade to be seen, but slightly distorted.[3] Another, less monumental work is that of Polish artist Piotr Janowski, who wraps derelict buildings in aluminum foil in order to bring attention to Warsaw’s lack of affordable housing. He also, knowingly or unknowingly echoing Jeanne-Claude and Christo, says that the installation is his way of bridging the past and future, and “symbolically make [the city’s] destroyed beauty reborn.”[4]

Berlin is now one of the largest, wealthiest, and most visited cities in Europe, having been reborn from the ashes of the carnage of the twentieth century in an unprecedented recovery. Serving as both a footnote to the ruined, divided, old Berlin and the foundation of the new, united World City is Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s Wrapped Reichstag, which symbolizes the new era and the optimism it brings. Germany, and the world, are still reeling from the effects of the World Wars and the Cold War, but their work reminds us that the painful events are in the past and that there is something new on the horizon.

[1] Scott, Nate. 2015. “Refuge of Last Resort: Five Days inside the Superdome for Hurricane Katrina.” For the Win. For The Win. August 24, 2015. https://ftw.usatoday.com/2015/08/refuge-of-last-resort-five-days-inside-the-superdome-for-hurricane-katrina

[2] The New York Times. 2021. “An Emotional Recovery (Published 2006),” 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/26/sports/football/26saints.html.

[3] “SANAA’s Rippling Glass Façade Bookends ‘La Samaritaine’ Restoration.” 2019. Designboom | Architecture & Design Magazine. March 10, 2019. https://www.designboom.com/architecture/la-samaritaine-paris-sanaa-department-store-edouard-francois-hotel-03-10-2019/.

[4] Jewell, Nicole. 2019. “Derelict Building Is Wrapped in Tin Foil to Protest Lack of Affordable Housing in Warsaw…” Inhabitat.com. Inhabitat. February 6, 2019. https://inhabitat.com/derelict-building-is-wrapped-in-tin-foil-to-protest-lack-of-affordable-housing-in-warsaw/.

Bibliography

Debord, Guy. Society of the Spectacle. Detroit, MI: Black & Red, 1970.

Douglass-Jaimes, David. 2018. “AD Classics: New German Parliament, Reichstag / Foster + Partners.” ArchDaily. October 25, 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/775601/ad-classics-new-german-parliament-reichstag-foster-plus-partners.

Frank Schirrmacher, “Den Reichstag verpacken?” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, (23 February 1994).

Greenberger, Alex. 2020. “Christo Dead: Famed Sculptor Dies of Natural Causes at 84.” ARTnews.com. ARTnews.com. May 31, 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/christo-dead-wrappings-sculptures-1202689250/.

Jelavich, Peter. “The Wrapped Reichstag: From Political Symbol to Artistic Spectacle.” German Politics & Society 13, no. 4 (37) (1995): 110-27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23736267.

Jewell, Nicole. 2019. “Derelict Building Is Wrapped in Tin Foil to Protest Lack of Affordable Housing in Warsaw…” Inhabitat.com. Inhabitat. February 6, 2019. https://inhabitat.com/derelict-building-is-wrapped-in-tin-foil-to-protest-lack-of-affordable-housing-in-warsaw/.

Monika Maron, “A Gigantic Plaything” [“Ein gigantisches Spielzeug”], Der Spiegel, July 3, 1995, pp. 24-25

Rogier, Francesca. “Growing Pains: From the Opening of the Wall to the Wrapping of the Reichstag.” Assemblage, no. 29 (1996): 44-71. doi:10.2307/3171394.

Scott, Nate. 2015. “Refuge of Last Resort: Five Days inside the Superdome for Hurricane Katrina.” For The Win. August 24, 2015. https://ftw.usatoday.com/2015/08/refuge-of-last-resort-five-days-inside-the-superdome-for-hurricane-katrina

Swartz, Anne. “Christo and Jeanne-Claude.” The Encyclopedia of Sculpture (2004): 317-320.

The New York Times. 2021. “An Emotional Recovery (Published 2006),” https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/26/sports/football/26saints.html.

The New York Times. 2021. “Christo Sets His Sights on Wrapping Reichstag (Published 1993),” https://www.nytimes.com/1993/01/07/arts/christo-sets-his-sights-on-wrapping-reichstag.html.

The New York Times. 2021. “Wrapping the Reichstag: Christo Gets a Go-Ahead (Published 1994),” https://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/26/arts/wrapping-the-reichstag-christo-gets-a-go-ahead.html.

“Christo and Jeanne-Claude.” Christojeanneclaude.net. 2021. https://christojeanneclaude.net/artworks/wrapped-reichstag/.

“SANAA’s Rippling Glass Façade Bookends ‘La Samaritaine’ Restoration.” 2019. Designboom | Architecture & Design Magazine. March 10, 2019. https://www.designboom.com/architecture/la-samaritaine-paris-sanaa-department-store-edouard-francois-hotel-03-10-2019/.

“The Public Art Project That Entranced Post-Cold War Berlin.” 2019. BBC News. June 12, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/stories-48597551.

OBL/QUE

OBL/QUE is an architectural conservation journal seeking to explore some of the more obscure and niche topics within preservation, including the sociocultural implications of architectural heritage and less formal and conventional means of preserving and engaging with it. This journal is based in the Harvard Graduate School of Design and is in partnership with Northeastern University and other schools and individual architects. Volume 3, which I contributed to as an visual and text editor, came out in the autumn of 2020, and is free to download at the link below.

Click here to view OBL/QUE‘s website and download a free copy of Volume 3.

Planted Meadow Design

Long Island Planted Meadow Design

Residential lawns, despite seeming innocuous, are one of the largest contributors to environmental damage in the West. According to landscape architect Owen Wormser in the 2020 novel which inspired this project, Lawns into Meadows: Growing a Regenerative Landscape, the average gas-powered lawnmower creates more carbon dioxide pollution in a single hour (maybe half of your weekend mowing session) than a car using an entire tank of gas. Factoring in the effects of fertilizer and other upkeep on the groundwater and local wildlife, the way that continuous maintenance weakens both the soil and the grass itself, and carcinogenic properties of many of the commonly used lawn treatments such as gylphosate, lawns overall are a serious issue worthy of our consideration as architects. And this is not to mention all of the social and cultural implications of “lawn culture”.

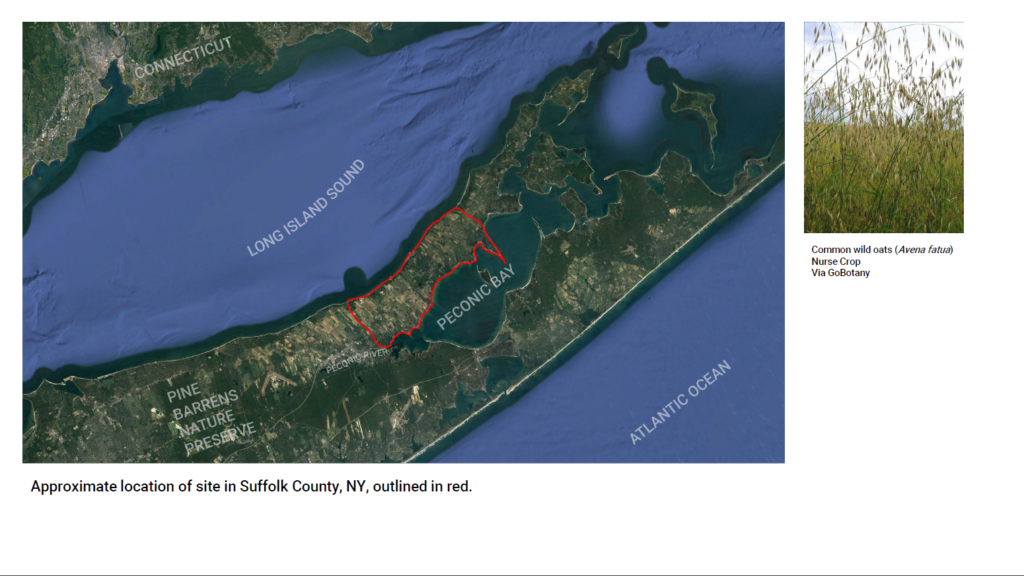

This project is a hypothetical proposal for transforming a typical lawn on eastern Long Island, New York, into a planted meadow which uses native plants, aimed at rehabilitating the soil with phyto-remedial techniques.

The preparation for this design included some site analysis and precedent study. Thankfully, I know this area well and had the chance to go out and study it during my time working on this project so I was able to get a good understanding of the needs of the site and the types of plants that would thrive here. This region is characterized by having tall, rocky-cliffs in the north and west that give way to low-lying, flood prone land, and being very densely populated with a strongly entrenched culture of well-kept lawns. The soil here is slightly acidic, moist, and well-drained. According to the Long Island Pocket Guide for Landscape Soil Health from Cornell University, the soil association for the area is made up of soil types known as Carver coarse sand, Plymouth loamy sand and Riverhead sandy loam. The average temperature ranges from below freezing in the winter to just above 80°F in the summer, and the island’s cold hardiness zone is 7. Due to Long Island’s coastal location and generally more temperate climate than the rest of the northeast, it is considered a transition zone where both cool and warm-season grasses thrive, although cool-season is preferred. The meadow planting is assumed to be in the backyard of a fairly large, flat property, which allows for more height variation than a front yard.

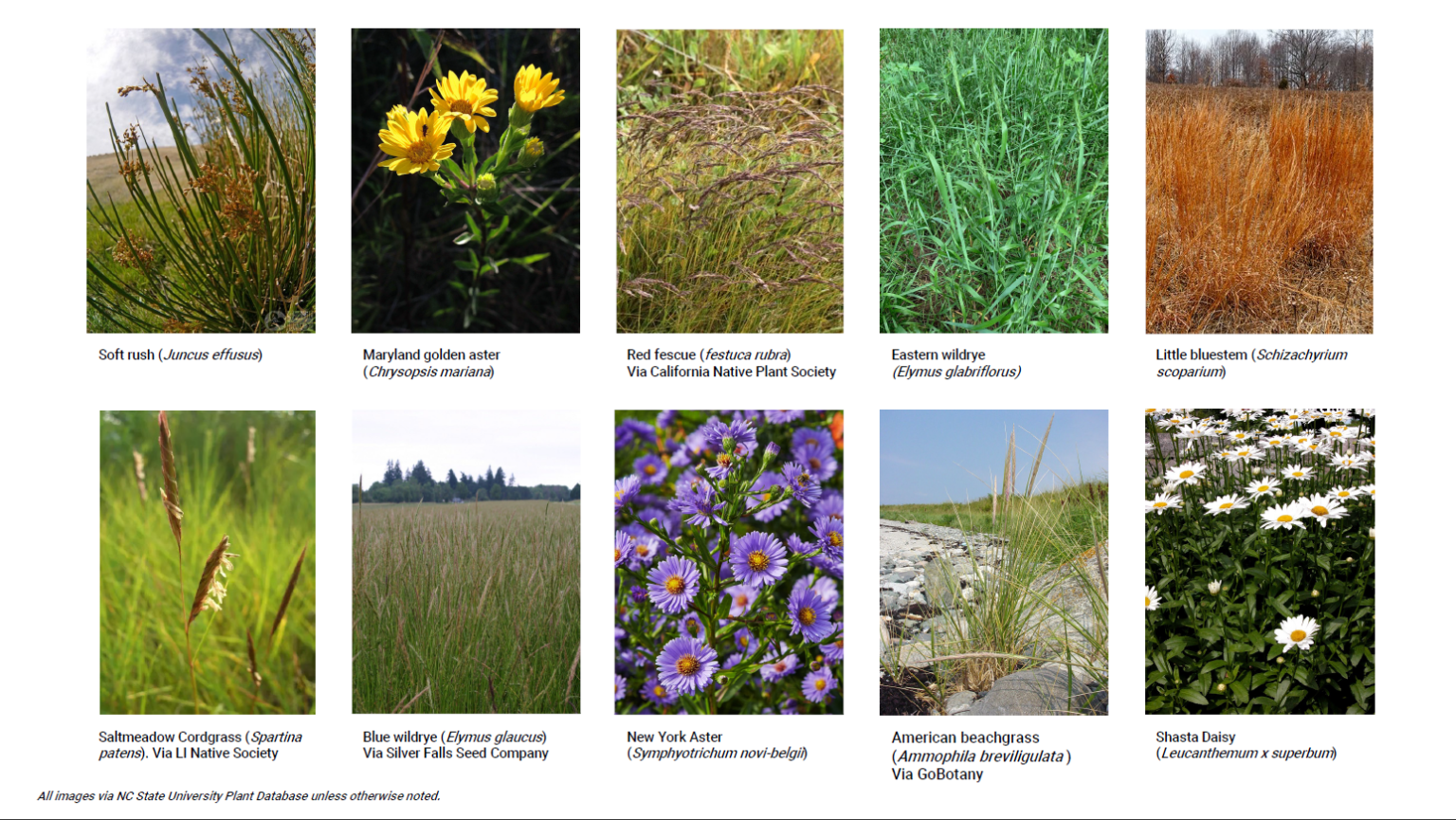

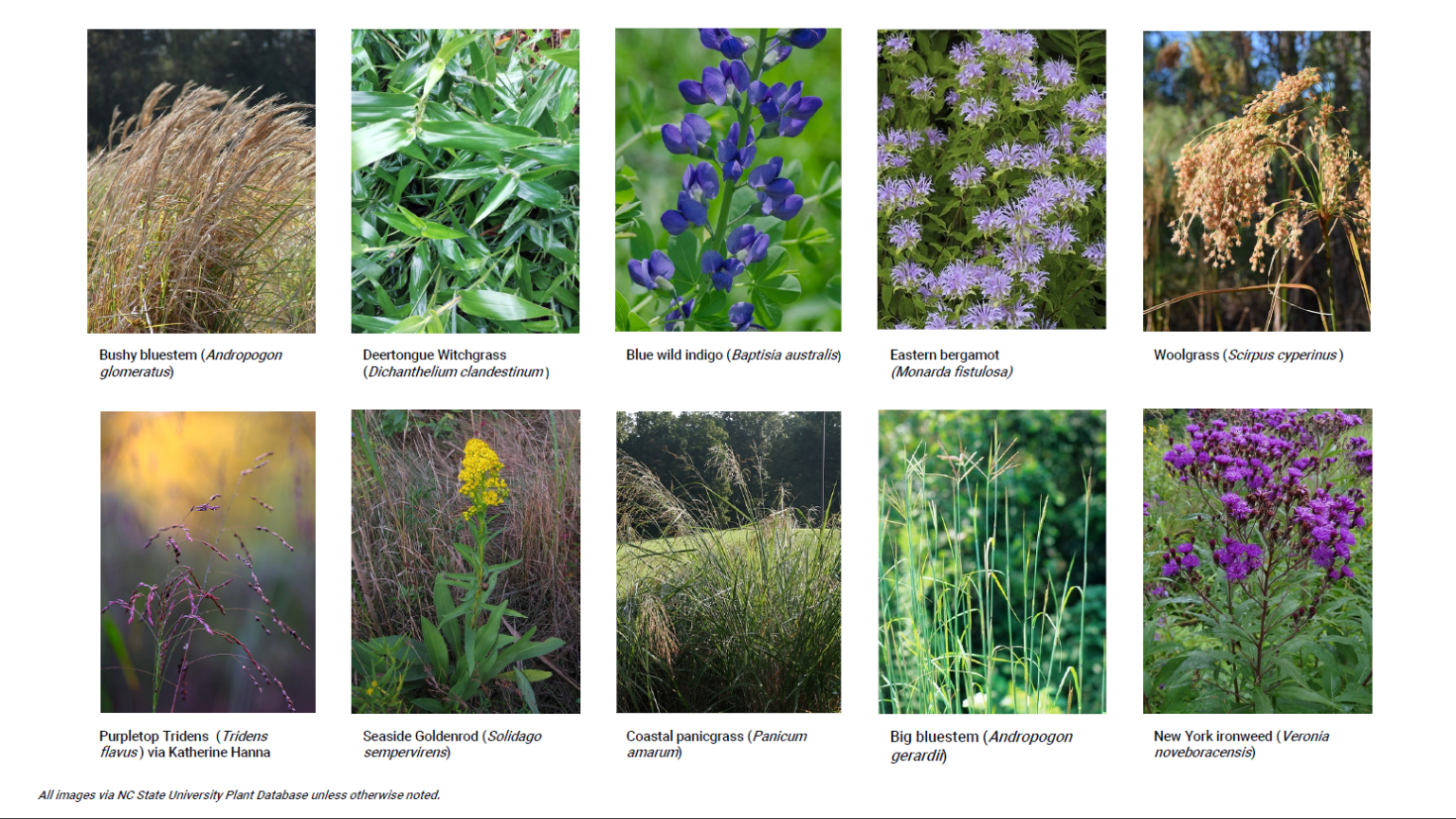

Given these conditions, the plants chosen are tolerant of poor soil conditions, adaptable to temperature changes, high moisture and precipitation, and useful for the existing wildlife which includes deer, gulls, wild turkeys, and butterflies. Many of these plants, such as the eastern bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) and the woolgrass (Scirpus cyperinus) provide larval hosting for migrating butterfly species and food for the declining bee population. Also, a few of these plants perform ecological services including nitrogen fixation in order to heal the soil which has been battered by a century of urban sprawl and harmful lawn treatments. Inspiration is taken from local beaches and parks such as Cupsogue County Park in Westhampton and Cedar Beach Nature Preserve in Mt. Sinai as well as existing planted meadows such as the Theodore Roosevelt Audubon Center in Oyster Bay. In order to preserve local identity and visually tie the garden to its surroundings all of the plants are native to the area except for one, the Shasta Daisy (Leucanthemum x superbum), although it is a common foreign plant already used in the area. The plants are divided into three main layers, as a high layer with many of the most vibrant and attractive plants, a low layer that is more subdued but still visually interesting and whose bloom times complement those of the high layer, and a groundcover that keeps a consistent backdrop for the project.

See my data, sources, and other information in the spreadsheet below:

Powered By EmbedPress

Chain Forge Market and Hotel

Cities and towns should be shaped by physically defined and universally accessible public spaces and community institutions; urban places should be framed by architecture and landscape design that celebrate local history, climate, ecology, and building practice.

Charter of the New Urbanism, 1993

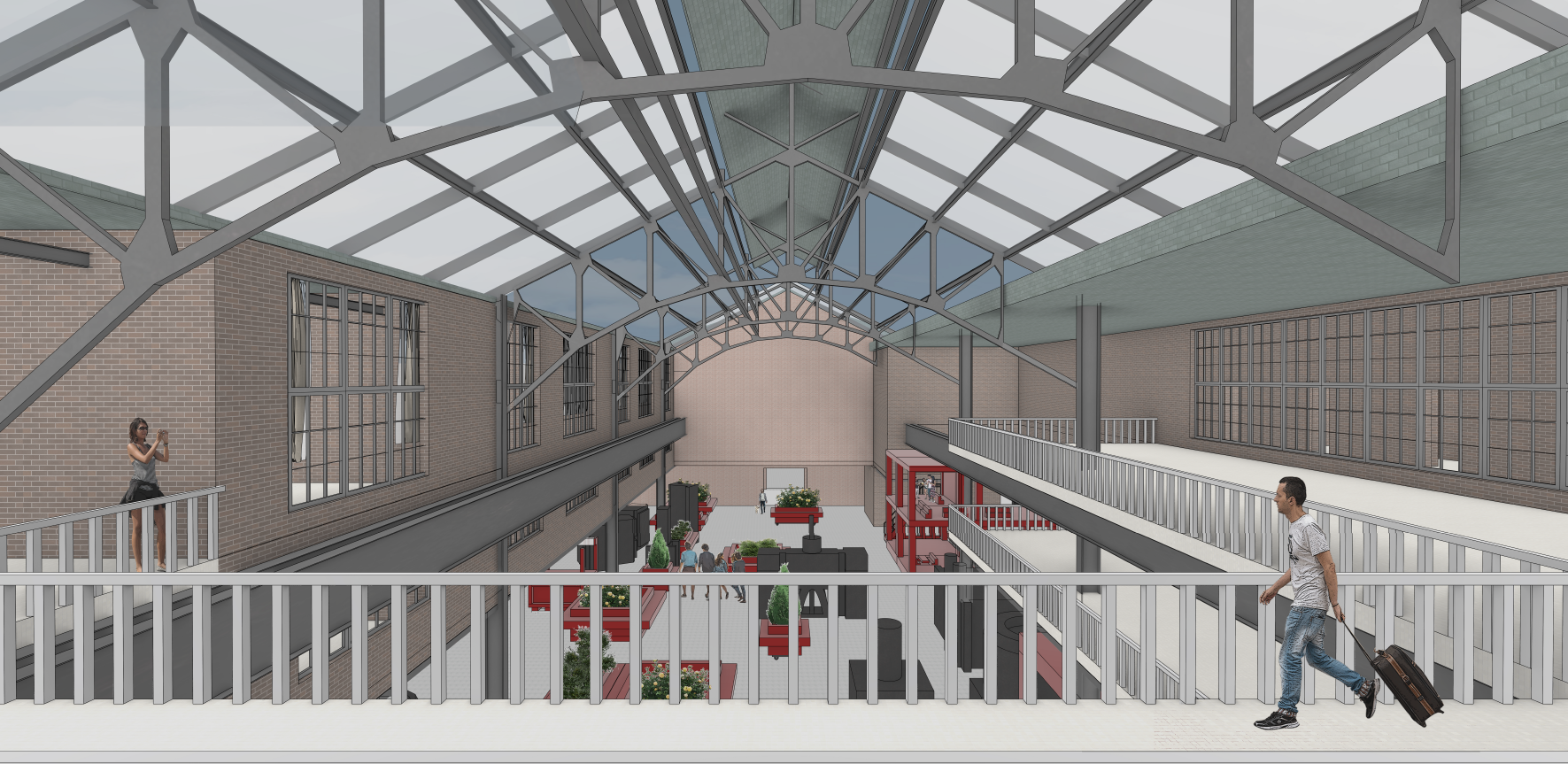

The Chain Forge Smithery at Charlestown Navy Yard served as one of the forefronts of American naval innovation from its construction in 1903 to the Navy Yard’s decommissioning in 1974. Among other important roles in naval history, this building was the site of the invention of the Die-Lock anchor chain in 1924 and had a hand in the Lend Lease program of 1941-1945, contributing to the Yard’s ship construction. The building, with over one hundred industrial machines remaining inside, has sat dormant from 1974 until recently, when a hotel proposal was greenlit for the site. This hypothetical project, completed in a studio focusing on architectural conservation and reuse, proposes a way to integrate this hotel into the urban fabric while also inviting Charlestown residents back to the Navy Yard, as they are now separated from their old workplace by a highway, the stigma of tourism, and a lack of community amenities. A major goal of this project is to spur interaction between various demographics that would otherwise not interact, namely tourists, businessmen, and locals, which will hopefully change the perception locals have of tourism and the perception tourists have of locals.

Through a phased development timeline, the Chain Forge Smithery will be transformed into a combination of a flexible community space, a public market, and a hotel. The factory floor, approximately 40,000 square feet, is almost completely open save for a selection of the machines and a series of mobile “follies”. These follies range from a simple moving platform to a fully enclosed, multi-story miniature building within the shell of the factory, and are the model for a dynamic public market that can be rearranged at will. These follies – both to demonstrate their “newness” in contrast (and subservience) to the old and to call back to the yard’s history – are made of a dark red metallic material reminiscent of the Gleaves-class Destroyer ships designed and constructed at Charlestown during World War II. All of these follies are rentable, specifically targeted towards local small businesses, farmer’s markets, and startup incubation. They are able to be combined and arranged to suit whatever the renter’s needs are.

This model will persist on its own for about one to two years, with the follies and more permanent structures slowly coming in over time. Only then, once this space is established as a valid community center, will the commercial development come in. Using reclaimed brick from demolition elsewhere on the site, the upper factory floors will be given over to the hotel program. The hotel features large factory windows, balconies, and catwalks the prompt the hotel guests to be “good neighbors” to the marketgoers and vice versa.

View the entire project below:

Powered By EmbedPress

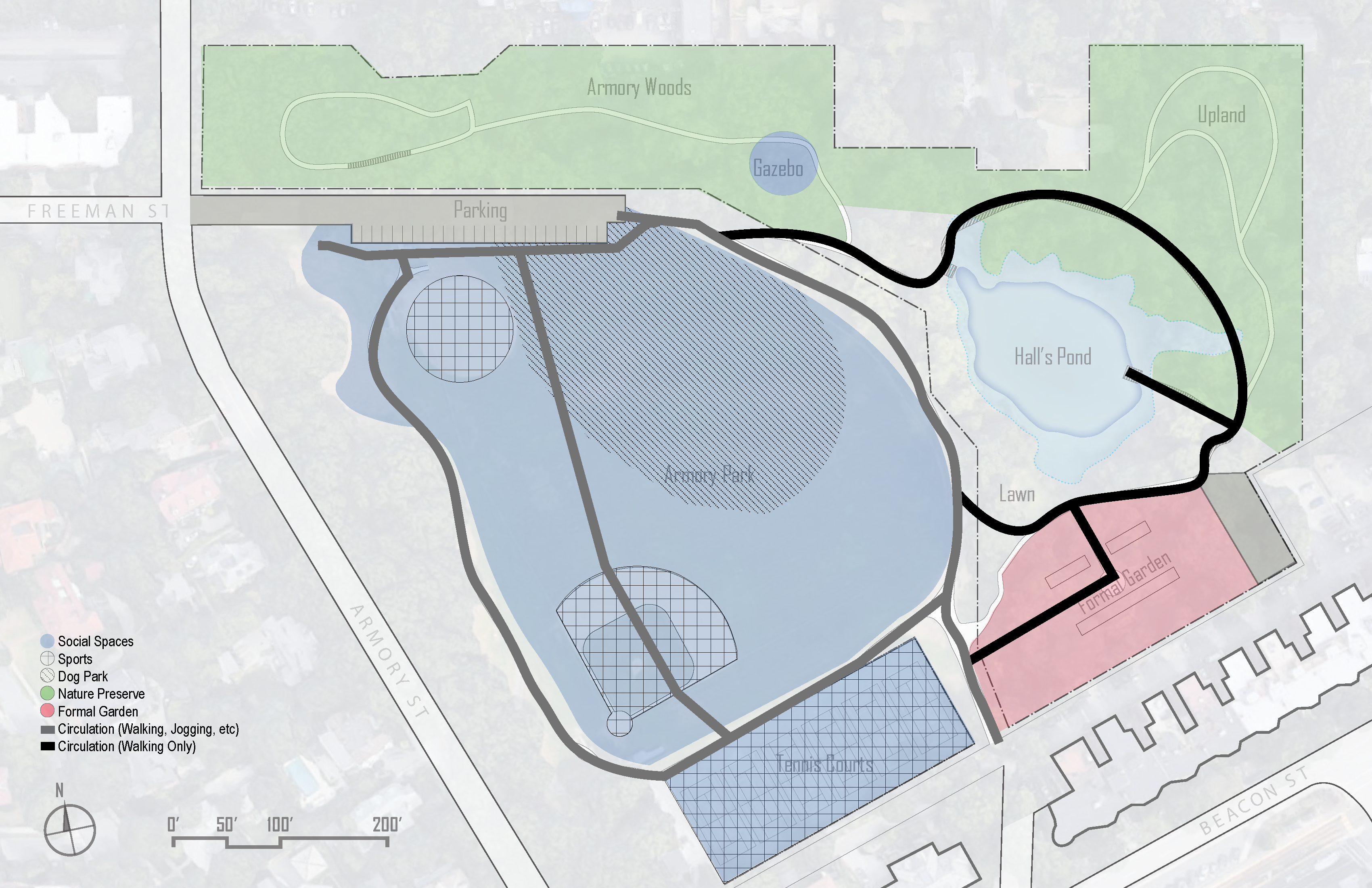

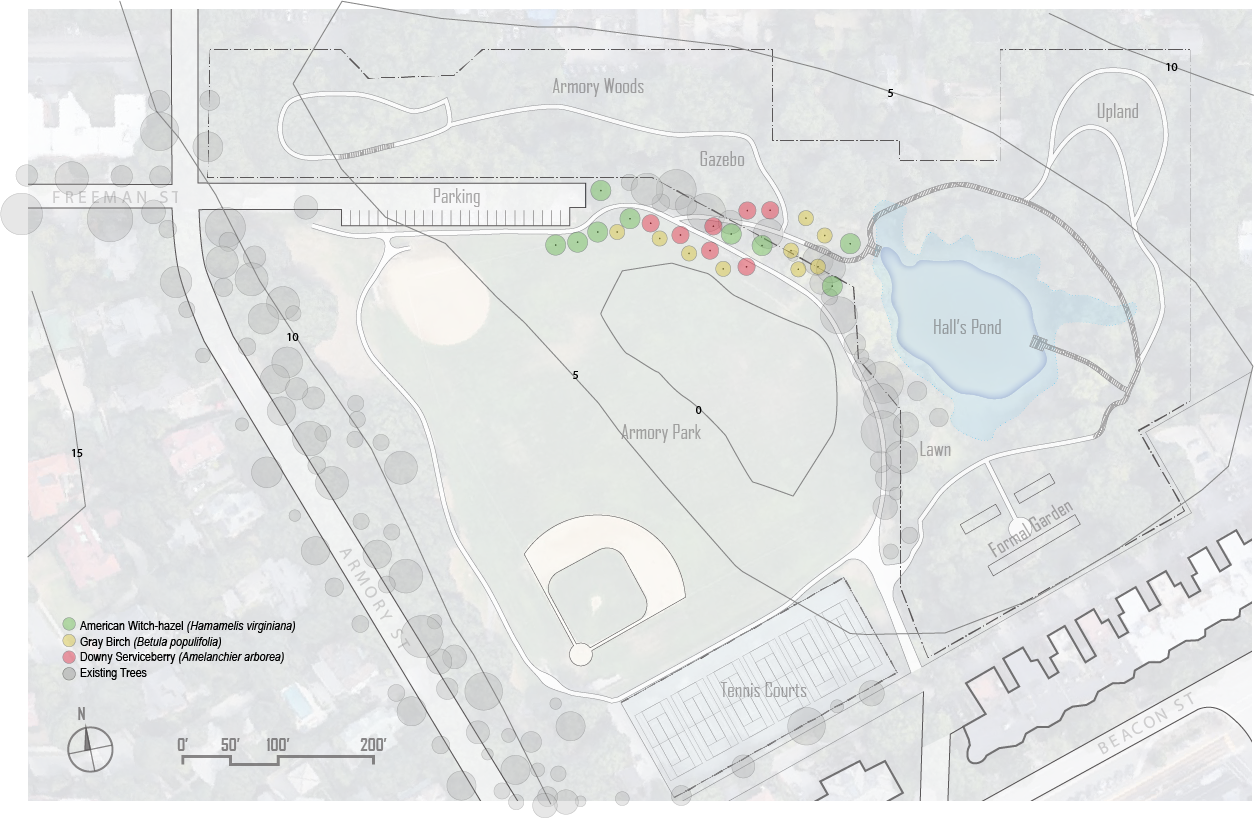

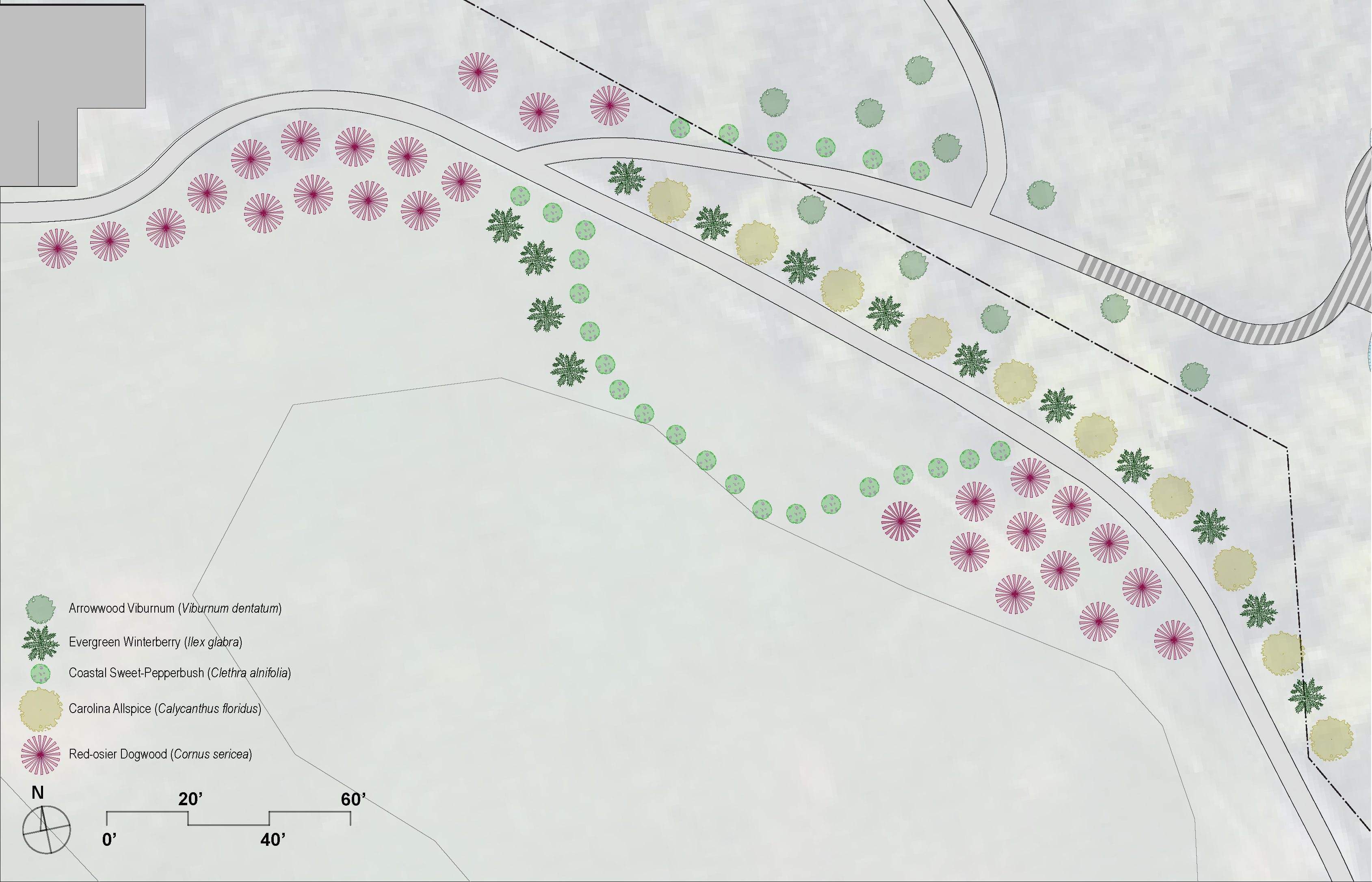

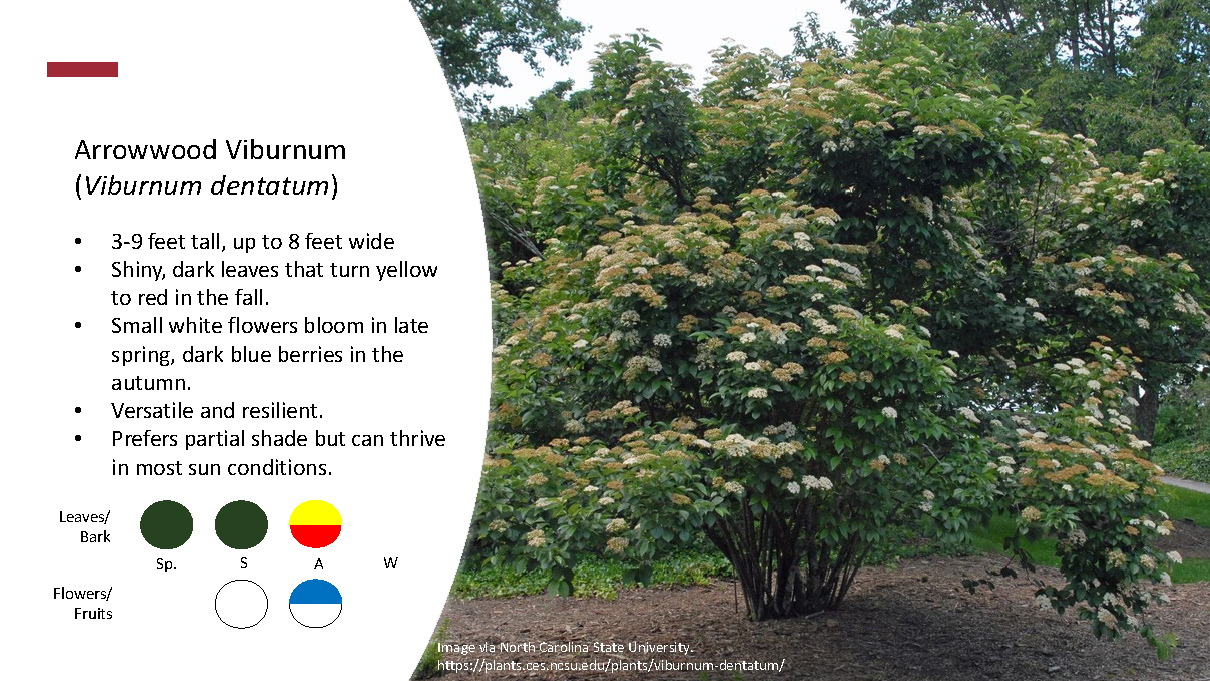

Hall’s Pond Planting Scheme

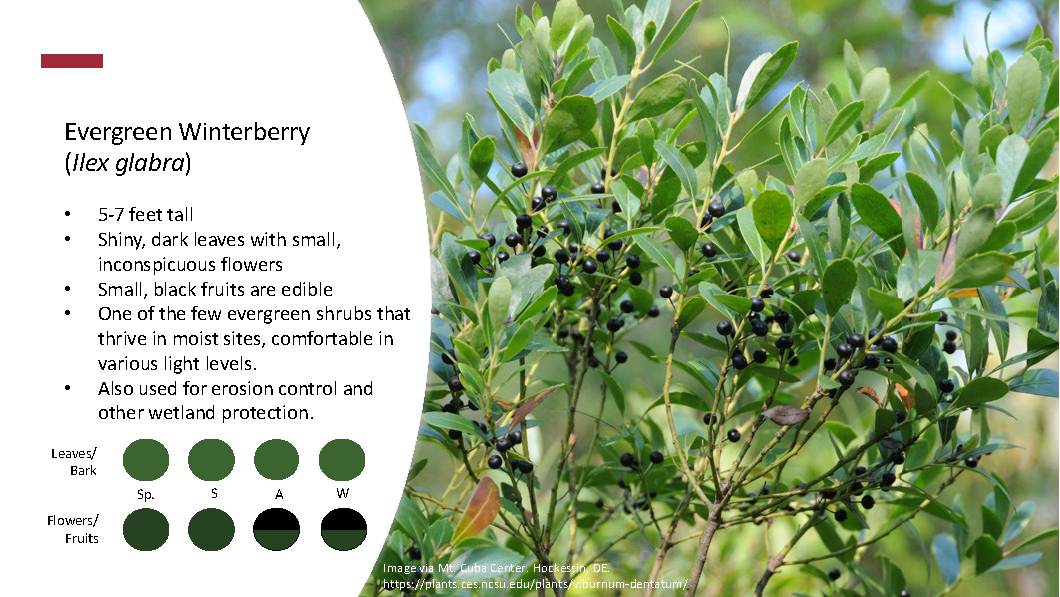

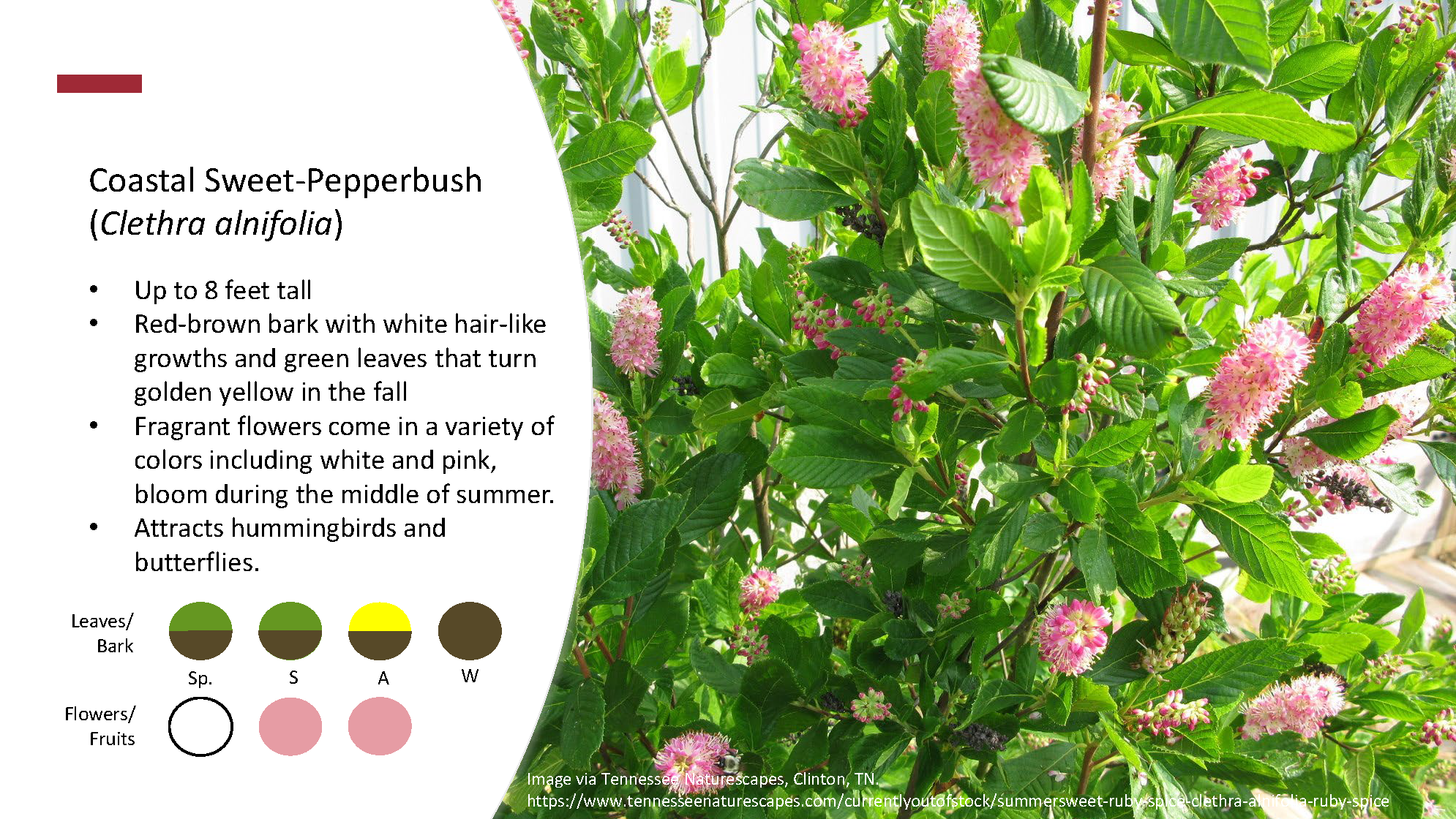

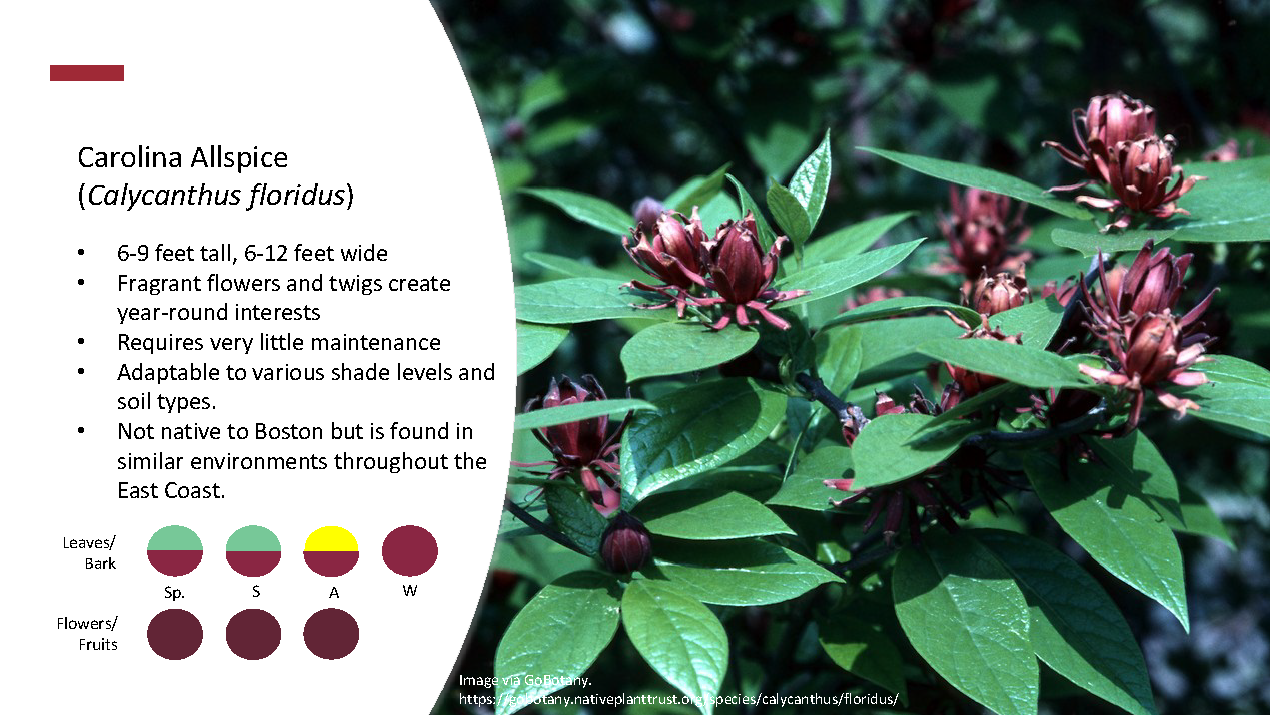

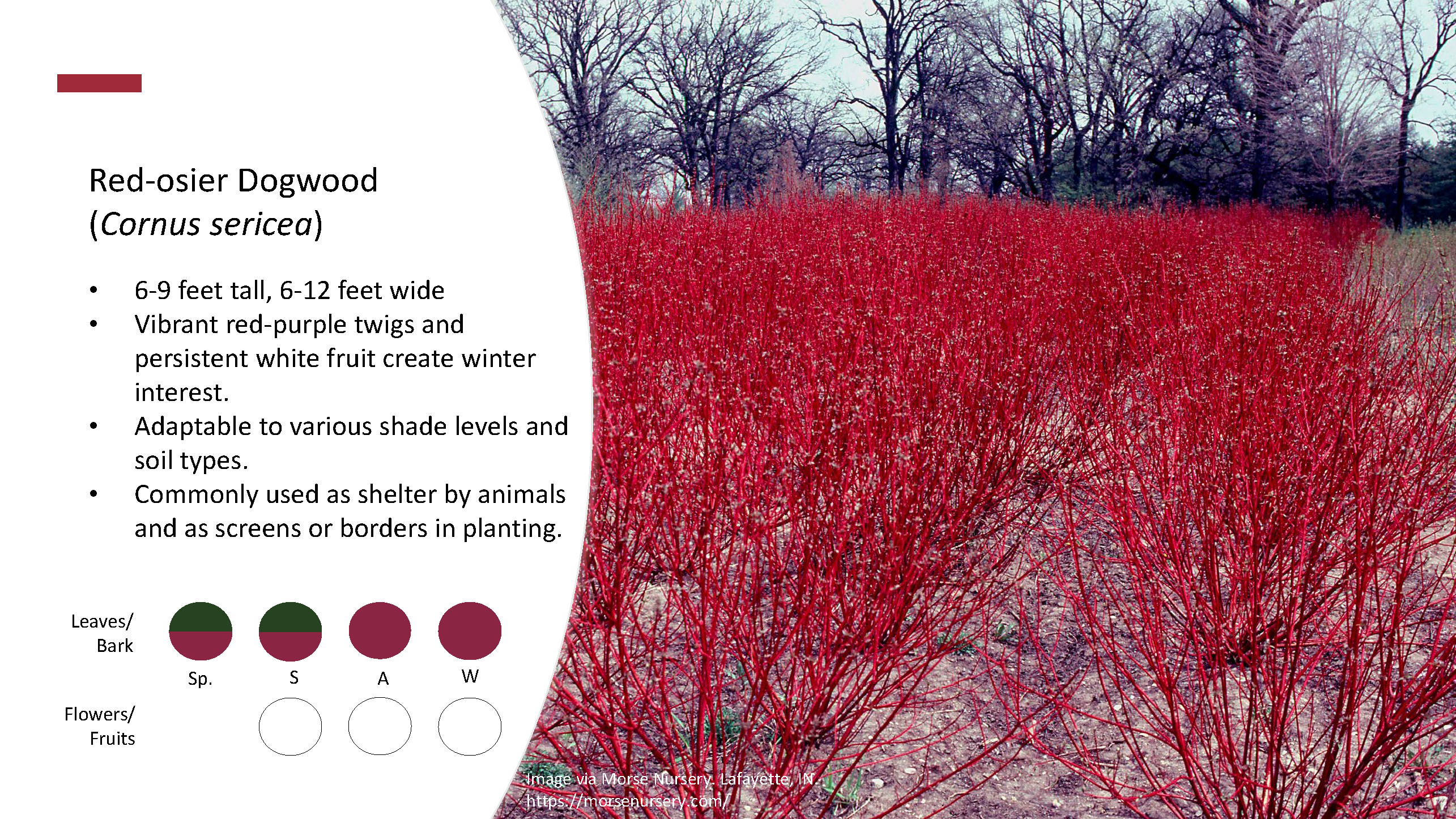

Hall’s Pond Sanctuary is a 3.5 acre nature preserve in Brookline, Massachusetts. The pond is connected to the adjacent Amory Park by a pathway which links it to the parking lot in the north and Beacon Street in the south. This is a simple tree and shrub planting scheme for the stretch of path between the parking lot and the pond entrance, along with fact sheets on each of the five selected shrub species.